Python virtual environments

A frined of mine was signing the prasises of Python virtual environments recently so I decided to try and figure out what he was talking about. Turns out creating a virtual environment is pretty straightforward (as least in Anaconda) and super useful.

Some Resources:

-

https://uoa-eresearch.github.io/eresearch-cookbook/recipe/2014/11/20/conda/

-

Why you need Python environments and how to manage them with Conda

Answers to some simple questions

Really, I’ve just been monkeying with separate environments for a couple days so answers to simple questions are really all I got at this point.

What is an environment?

A named, isolated, working copy of Python that that maintains its own files, directories, and paths so that you can work with specific versions of libraries or Python itself without affecting other Python projects. Virtual environmets make it easy to cleanly separate different projects and avoid problems with different dependencies and version requiremetns across components.

Why do I/do I need one?

-

Maybe you’re testing somebody else’s application that has lots of library dependencies and you don’t really want to install all those libraries in your base environment.

-

Maybe you’re collaborating with somebody who’s project requires a specific version of Python and you don’t want it to conflict with your prefered Python version.

-

Maybe you want to share a project or app. It works great on your system but to make things idiot-proof for your potential users you might want to make sure they are running it the same way you test it. Then you might want to make sure they run it from the proper environment. See the Import and export a conda environment section.

But do I really need separate environments?

Maybe not. I just had a hallway conversation with 2 colleagues:

One was adament that you should create a virtual environment for every project using a .yml file then, upon project completion, delete the virtual environment because it can always be recreated with .yml file. This way you don’t clutter your system with packages and libraries that might be project specific and the virtual environment helps ensure reproducability of the work.

The other felt that virtual environements are clunky, have a tendency to muck up your system with mulitple copies of the same library, and aren’t really necessary unless your dealing with lots of versioning conflicts…which in this colleague’s experience was kind of rare. This individual prefers to create virtual environments sparingly and only in the small number of cases where a versioning conflict actually arise.

I can’t say I have a good sense of whether or not virtual environments will become part of my regular workflow…but I’m kinda glad I at least know what they are and how to create them.

My Example:

Overview

I have a machine learning application that I’m working on with a colleague. In this case, my co-author is doing most of the heavy lifting and I’m mostly just testing code, interpreting results, and doing the writing. I need to be able to run his code which depends on a bunch of ML and AI libraries. Also, my co-author uses Python 3.5 while my Anaconda root environment is currently using 3.7.

Create the environment

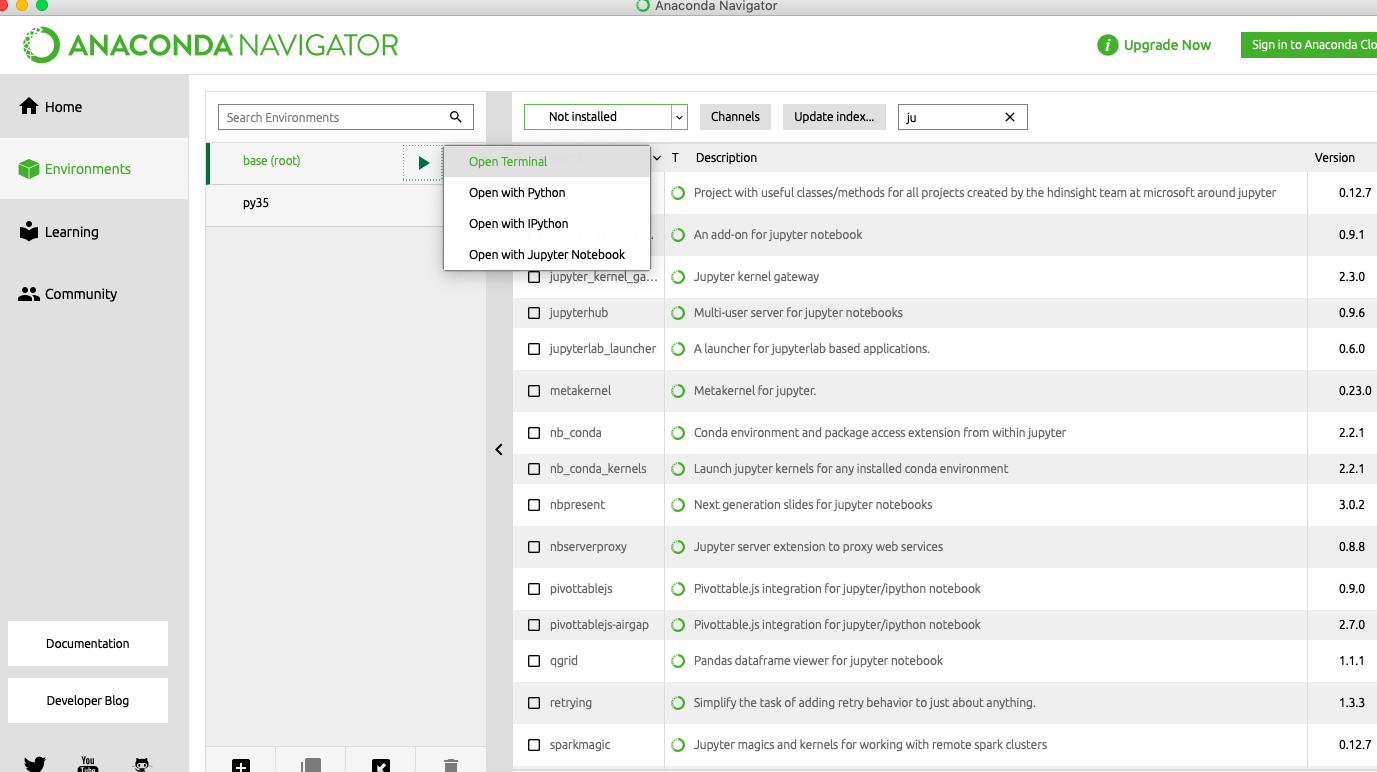

Per the Conda documentation, creating a virtual environment is rediculously easy. Open the terminal (I prefer to open a command prompt from with the Anaconda Dashboard because - for a variety of Windows related reasons that I don’t like - this is how I have to do things at work where Macs are VERBOTEN!!) and do:

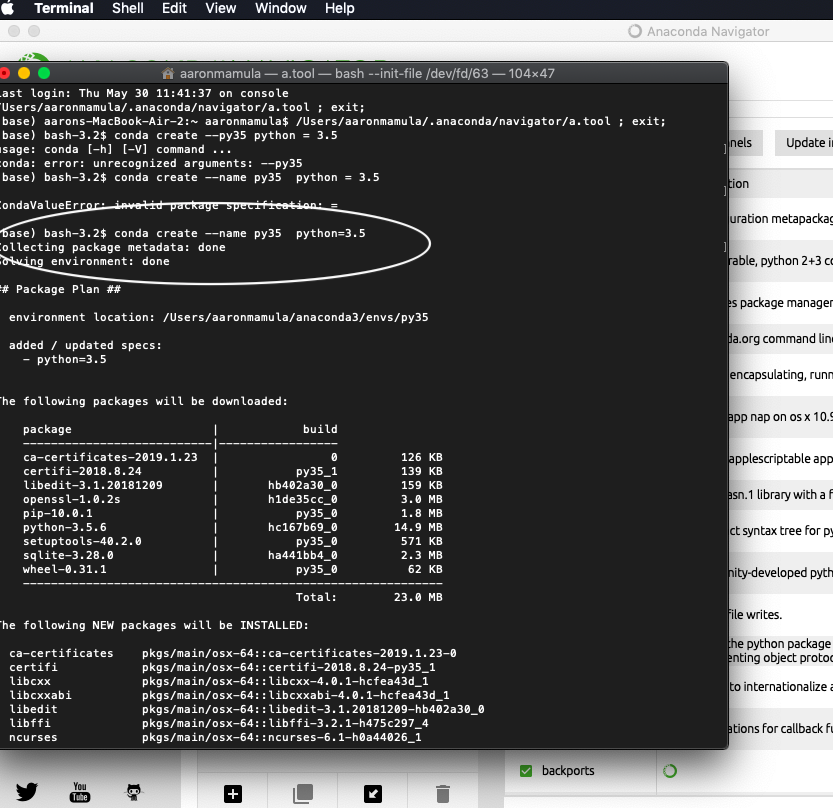

conda create --name py35 python=3.5

In this case, I’m creating a virtual environment called py35 that will use Python version 3.5. Note that I have not yet declared any libraries to be included in this environment.

You’ll also likely notice that I messed up the really simple command line inputs a few times before I got it right…I left them in the screen shot to add some authenticity to the blog. Please don’t let my shyte coding distract you.

Also notice, that even though I have not specifically installed any packages/libraries in this environment, the environment is created with a BUNCH of stuff in it. It seems that by default Python/Anaconda will create a new environment with all of the packages in the base environment.

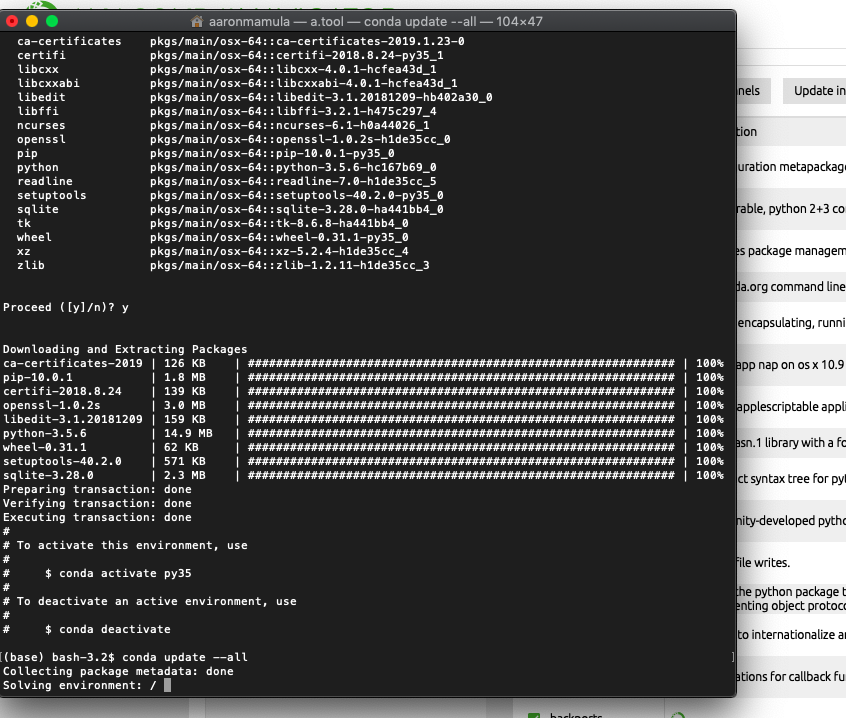

Activate the environment

Again, Per the Conda documentation I can switch over to using my new environment with:

conda activate py35

Add some stuff to the environment

Here is the header line from a Jupyter Notebook that my coauthor send me:

import pandas as pd

import pandas_profiling

import numpy as np

from datetime import datetime

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.ensemble import AdaBoostRegressor

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

from sklearn import preprocessing

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, r2_score

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

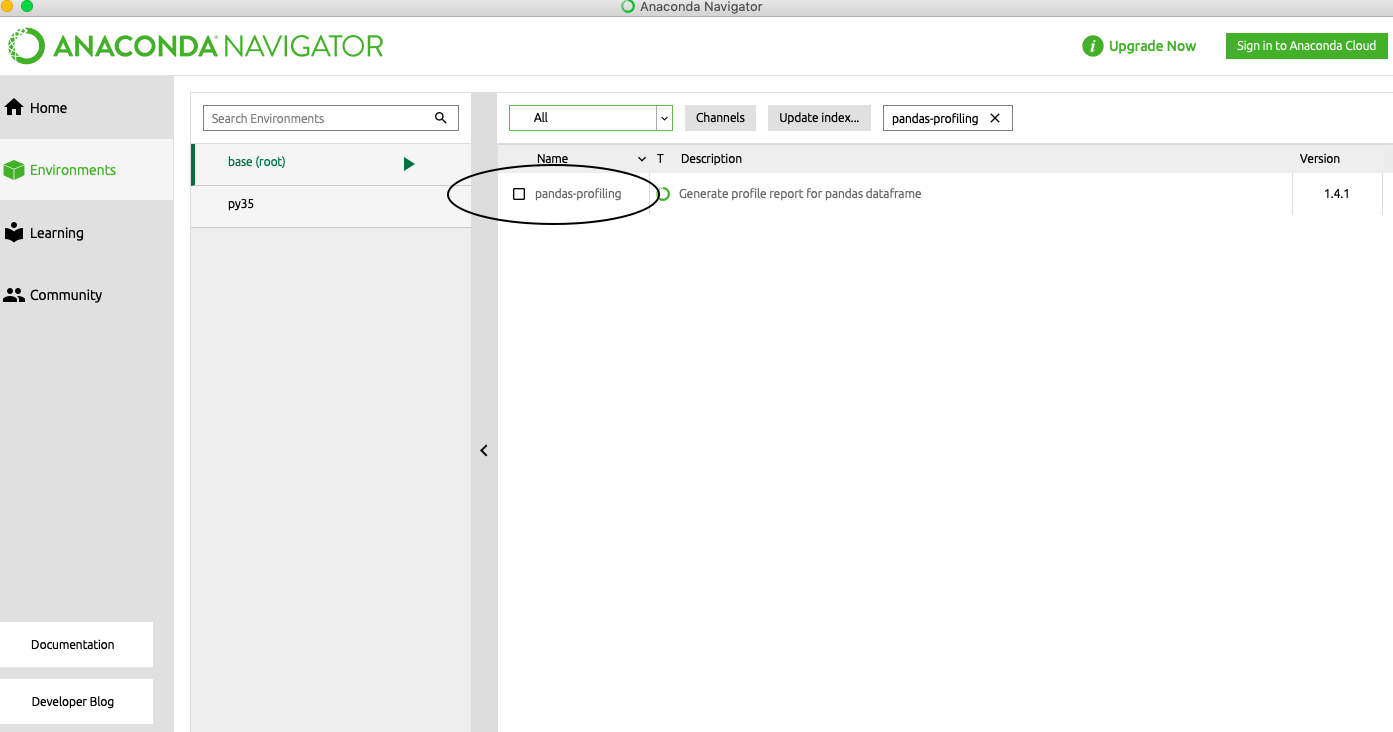

Right off the bat I’m pretty sure that I’ll have to install the pandas-profiling library to my environment. This happens just the same way I would add a package to the base environment: Open the terminal/command line and,

conda install pandas-profiling

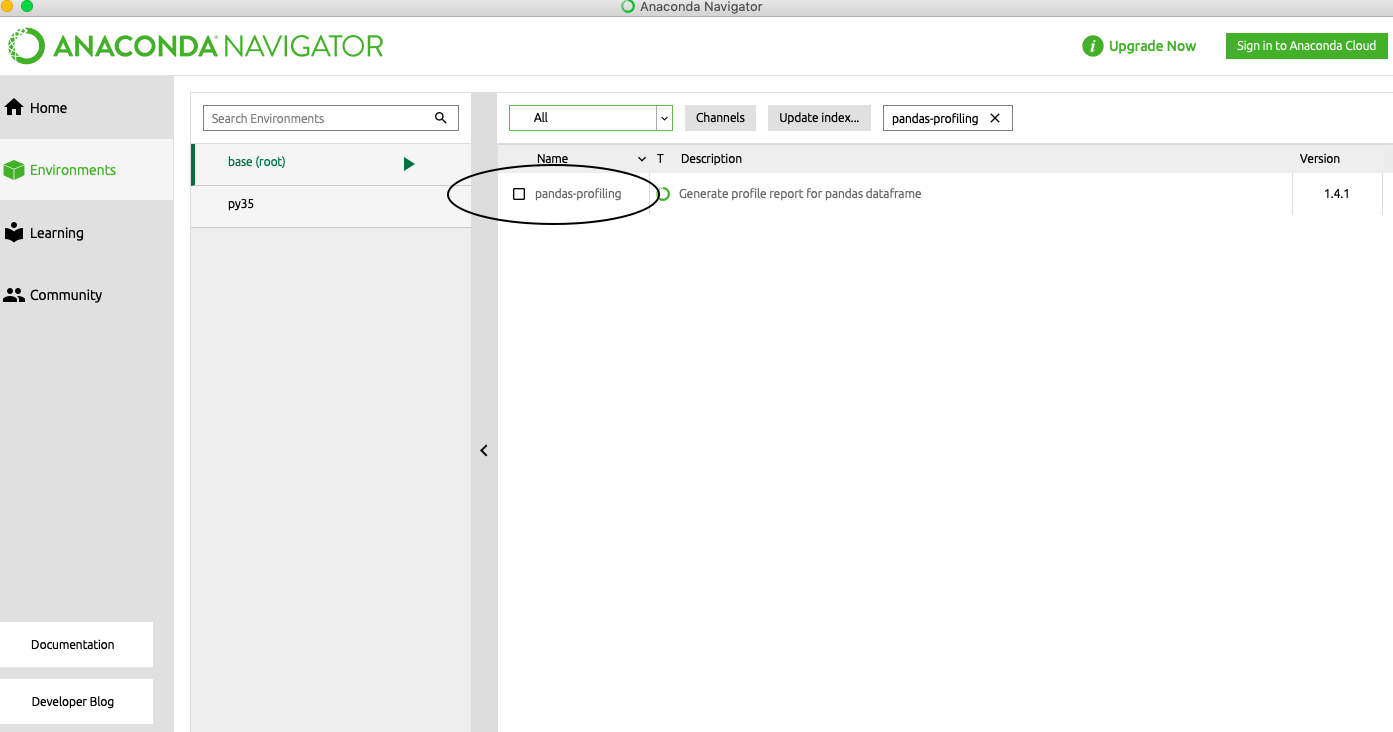

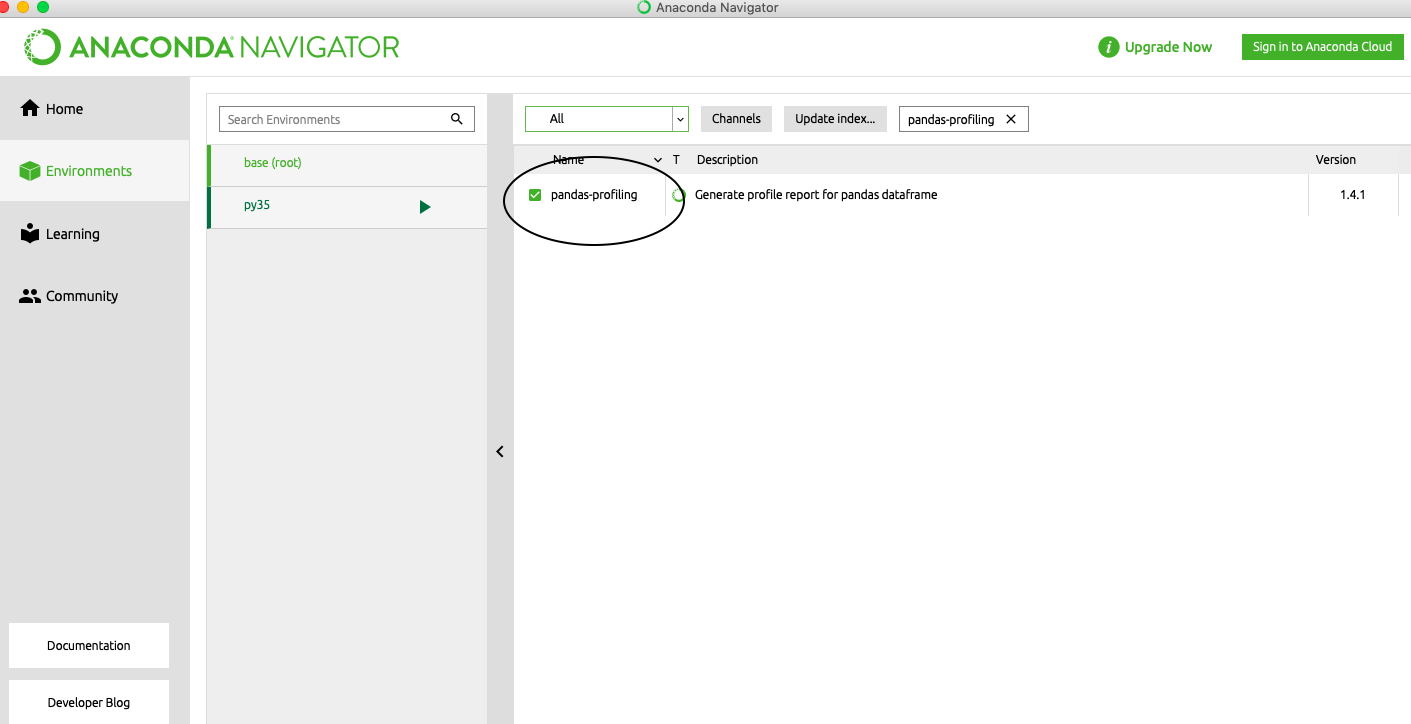

Since my py35 environment is active, Anaconda will install this package in the py35 environment but not the base(root) environment. Here is one way we/I can verify this fact: The screen shots below demonstrate that, in the Anaconda Dashboard, we can see which packages are included in each environment. Here you can see that pandas-profiling is not included in the base environment but is included in the py35 environment.

More on installing packages in a virtual environment

According to the Conda repository one should add all necessary packages to an environment at once (presumably when the environment is created). While this sounds perfectly reasonable to me, it also sounds like a practice I’m not likely to adopt any time soon. At the moment the major utility I can see from working with virtual environments is having a separate work space available for projects where I need to be able to run or test other people’s code. In this case, at least in the short run, I’m probably more likely to follow the iterative process of:

- look at the code

- create a virtual environment

- identify any packages/libraries/versions that I know right away will need to be added and add them

- try to run the code

- get an error because my environment is missing a library

- add the library

- repeat 4-6 until things work.

Looking forward

I realize that I’ve covered only the most basic and pedestrian elements of create a Python virtual environment here. Next week I’ll try to follow up with some of the cooler elements of virtual environments (creating environments from and .yml file, exporting an environment to a colleague or collaborator).