Affordable housing in santa cruz part 2 more thoughts on accessory dwelling units

In my last post I tried to set the stage for a discussion (one I’m pretty much just having with myself at the moment) on regional housing policy in Santa Cruz County. For whatever it’s worth, I also blogged about this a while back on The Samuelson Condition Blog. Today’s discussion on Accessory Dwelling Units will be decidedly more nuanced than what I wrote a year ago and, as any good Bayesian would when confronted with additional data points, my opposition to subsidized ADUs has softened somewhat.

In my last post I was trying to make the point that a lot of specific policy recommendations related to provision of affordable housing have gone unevaluated because of the difficulties involved with analyzing policy choices when desired outcomes are not precisely defined. An example of a policy that I think deserves some scrutiny, but which has received very little, is the strategy of cities and regional housing authorities to subsidize construction of ADUs.

In this post I’m primarily interested in talking about how we should evaluate proposals to spend public money on subsidizing Accessory Dwelling Units.

And for purposes of clarity for the uninitiated, Accessory Dwelling Units are basically small additions to existing houses (often times turning a garage or shed into a studio apartment) usually for the purposes of renting out. Also sometimes called ‘Granny Flats’ or ‘Mother-in-Law’ units as, in addition to renting and ADU out, a homeowner might develop one in order to care for an aging parent.

Executive Summary and Roadmap

I have some lingering questions about the policy of subsidizing development of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) as a strategy for provision of affordable housing. I am very familiar with the conceptual advantages of ADUs for incentivizing densification in areas like Santa Cruz where geographic and regulatory restrictions on land development constrain the housing stock. As a matter of public policy, I’m not yet convinced that the benefits and costs of ADU subsidies have been evaluated in a rigorous enough fashion to know whether they constitute a responsible use of public money.

Although I will not be providing that thorough benefit-cost analysis here, I will be posing a few questions about ADUs that I think need to be asked an answered in order to understand their performance as a mechanism for helping deal with our ‘housing crisis.’

Here are a few issues I won’t touch on that probably warrant some deep thought sometime soon:

- ADUs might be a sensible strategy for dealing with the growth of our local UC (University of California Santa Cruz) since there are around 5,000 graduate students mostly living off campus. This number is likely to increase in the future and the number of undergraduates living off campus has also been increasing.

- Do ADUs subsidies encourage purchasing ‘more house’ than is prudent on the expectation of rental income? Does this expose local markets to elevated default risk?

- Relatedly, an often cited adverse impact of rising property values is long-time residents getting ‘priced out’ of their neighborhoods. As an economist I don’t usually associate willing sellers in a market with adverse impacts but, since the sociologists do, it is worth recognizing that ADU subsidies or amnesty for unpermitted ADUs could help long-time residents stay in their homes.

Intro

In my experience two undesirable things happen when we pose policy questions in the flowery prose of consultants rather than the precise (often dry, boring) language of scientists.

The first is that unsubstantiated claims and mythology are allowed to slip into the discussion and create their own realities. Both the Economic Vitality Study and Housing Element document use as motivation for talking about affordable housing the claim that lack of affordable housing is linked to homelessness. I’ve also seen this claim slipped into at least 3 local news stories on housing in Santa Cruz. This may be true but it sure as hell isn’t obvious. When presenting a claim that is neither obvious nor intuitive, most people would feel compelled to support it with evidence but no such support exists in the two documents I referenced. I note that Menlo/Atherton and Carmel California both have some of the most expensive real estate in California and neither has a particularly acute homeless problem.

Because we’ve framed our affordable housing discussion as this amorphous blob of sustainability, diversity, and equitability people often don’t bat an eyelash when somebody makes a wholly unsupported claim like, ‘it is widely accepted that our chronic homeless problem is exacerbated by the housing crisis.’

The second is that it leads to the development of policy and strategy that can never be evaluated. My experience with consultants is that they tend to like to work backwards. That is, they come up with broad set of policy recommendations that represent the current thinking in their field (for City and Urban Planners it all about urban infill, adaptive re-use, mixed use, green infrastructure, etc.) then they work backwards to a problem formulation that accommodates all of these things.

By tying together a massive web of problems (access to transportation, resilience to climate change, promotion of socio-economic diversity though affordable housing) and solutions (infill, ADUs, co-housing, etc.) you successfully create a strategy where no individual piece can ever be evaluated because you can always claims that removing any leg of the support topples the ‘integrated’ strategy.

One of the housing policy recommendations that seems to me to be very fashionable among Urban and Regional Planners but has largely escaped scrutiny (probably for the reasons I mentioned above) is the idea of encouraging construction of Accessory Dwelling Units as a strategy to provide affordable housing.

The Santa Cruz ADU program

In the interest of responsible stewardship of public money, I’m going to pick on a policy that has become basically a default setting for city and regional planners: encouraging construction of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs).

In Santa Cruz we have an ADU program that currently offers to waive around $13,000 in city permitting fees for people who agree to rent their ADU as ‘affordable housing’ (as defined by HUD: ~850/month for very-low income households and around 900/month for low income households). The City of Santa Cruz, through partnership with a local Credit Union, also offers special financial up to $100,000 for prospective ADU builders.

This is a great example of where we really need some precise understanding of what the ‘crisis’ is and when/how we will know the ‘crisis’ is over. Incentivizing ADU development is basically a stock recommendation of all city and regional planners these days primarily (I believe) because: there is very low political cost - everybody loves it because it looks like a win-win-win-win

- homeowners that want to develop an ADU get a little handout

- NIMBY homeowners that get barely visible ADUs instead of a low-income housing project nearby

- low-income renters are stoked to have any new supply on the market

- land conservationists are stoked to see supply come on line without new land getting developed

I’m not as opposed to ADU programs in general as people probably think. I am skeptical of their efficacy for the following reasons:

- It’s really easy for me to see exactly how homeowners benefit and by exactly how much

- Low income residents probably do benefit from incentivizing the addition of smaller housing units made available at below market rents. However, the exact magnitude and extent of those benefits is at worst uncertain and at best poorly articulated.

Items 1 and 2 together basically mean that we are spending public money on a program that bestows certain and quantifiable benefits on a group of relatively wealthy people while providing uncertain and ill-defined benefits to the group it is really supposed to be serving.

ADUs by the numbers

I honestly don’t have an issue with subsidized ADU development being part of a smart growth strategy. The problem that I articulated in my last post is that I don’t think we have a clear idea of how many housing units we are trying to supply, and at what price points we want to supply them, and what mechanisms (carrots v. sticks) we will accept for meeting those targets.

This makes it very difficult for me (or anyone else probably) to evaluate how good subsidized ADUs programs are relative to other possible expenditures of public money for addressing the ‘affordable housing crisis.’

A few questions:

- How many ADUs do we want?

- What, if any impact, would adding ADUs to the rental stock have on median rents?

- What is the feasible alternative to an ADU subsidy?

- What is the credible counterfactual?

- Is a subsidy better than a more rigid regulation?

- Affordable ADUs have an obvious benefit for seniors and single low income individuals. Presumably they have some residual benefits for low income families since they (maybe) reduce the total number of people in the ‘renter’ pool thereby putting some downward pressure on rents. Do we have any idea/estimate how many low income families on average can benefit from the addition of one ADU? An idea/estimate of the magnitude of benefit accruing to low income households from ADU construction?

Question 1: How Many ADUs Do We Want?

If we refer back to the Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments’ Regional Housing Needs Allocation we can see that Santa Cruz County is estimated to need 1,314 housing units in order to keep up projected growth. And if we refer to the Housing Element Table 4.7.1 we can see that county planners are forecasting 280 additional ADUs between now and 2023.

The RHNA is an estimate of how many housing units we need in order to keep up with forecasted growth. In other words, if we are in a housing ‘crisis’ now and we follow the recommendations of the RHNA we will ensure that the ‘crisis’ doesn’t get any worse between now and 2023. If 280 ADUs puts us on a path to being no less crisis-y in 2023 than we are now, how many more units do we need to add if we want to be out of ‘crisis’ entirely by 2023?

Question 2: How Do Local Real Estate Markets Respond to Supply?

One thing that particularly irritates me about subsidizing ADU development is that I can’t find, in any analysis anywhere, a good overview of local real estate dynamics.

How do markets respond to supply?

If we build ADUs and don’t designate them as low income housing, does their addition to the housing stock put downward pressure on rents? If so, how much?

Here is little taste of what I would like to see become a bigger part of our discussion on affordable housing. According to the 2010 and 2015 Deciennial Census supply and demand conditions in Santa Cruz County looked something like this.

| Unit Type | 2015 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 unit detached | 67,990 | 65,494 |

| 1 unit attached | 8,238 | 9,351 |

| 2 units | 3,339 | 3,917 |

| 3-4 units | 6,482 | 5,665 |

| 5-9 units | 3,769 | 4,154 |

| 10-19 units | 3,142 | 2,837 |

| more than 20 units | 5,704 | 5,698 |

| mobile homes | 6,099 | 6,707 |

| boats, RV, other | 271 | 179 |

| Total | 105,034 | 104,002 |

| Median Rent | 1,441 | 1,226 |

| Owner Occupied | 54,628 | 55,878 |

| Owner Vacancy Rate | 1.3% | 1.6% |

A little algebra here can get us a few more interesting numbers. We can ballpark the rental supply like this:

Total Owner Occupied Units = Total Owner Units X (1 - Owner Vacancy Rate)

Total Potential Rental Units = Total Housing Stock - Total Owner Units.

For 2015 we get:

\[54,628 = 0.997(OwnedUnits)\] \[OwnedUnits = 54,628/0.997 = 54,792\] \[RentalUnits = 105034 - 54792 = 50,242\]Using the same math for 2010 we get:

\[RentalUnits = 104,002 - \frac{55,878}{0.994} = 47,787\]Things do get a little complicated here because the 2010 observation of 47,787 rental units and median rent of 1,226 and 2015 observation of 50,242 rental units at a median rent of 1,446 are probably on two different demand curves (it seems likely to me that population growth and income growth probably resulted in a new demand schedule in 2015 at each price point on the 2010 demand curve). Because we are likely dealing with 2 different demand curves we can’t use price and quantity changes to infer the slope of the demand curve which complicates things. But let’s just do what I do on this blog all the time: pick some sensible number and proceed with it (we can alway do sensativity analysis later).

Let’s suppose that demand for rental units in Santa Cruz is relatively inelastic such that a $100 change in median rent results in only 50 fewer rental units being demanded.

If we assume that the slope of the demand curves remains constant (i.e. we are dealing with radial expansions of the demand curve), then one very basic thing we could do is assume an expansion of the demand curve over the next 5 years that is proportional to the expansion observed from 2010 - 2015. In that case, we would have the following demand and supply schedules in the rental market:

This clearly is not the most rigorous analysis we could conjure up but it does at least tell us one important thing:

- if we really believe that the Rent is Just Too Damn High

- and we want to cap rent by 2020 to 2015 levels

- and we think my assumed slope of the rental market demand curves is reasonable

then if we want to deflate rent using only market supply manipulations, we would have to supply around 60,797 rental units to the market in order to get rent stablized at median levels of around $1,441.

Question 3: What’s a Feasible Alternative to Subsidizing ADUs?

The language of alternatives is largely absent from our housign policy discussions in Santa Cruz. Our city and regional planners have embraced an “All of the Above” approach for dealing with the affordable housing ‘crisis.’ If you ask somebody, “is it better to build another homeless shelter or add 300 more rental units through ADU development?” you will most likely get told, “it’s not an either or situation.” You will then probably get lectured about the need for integrated solutions that offer a range of housing options respecting the distribution of income and age within the county.

This is of course nonsense. Obviously we need to address the underlying root causes of housing insecurity and pursue efficiencies and synergies whereever we can. But public money isn’t some bottomless well. We can’t just throw money at every idea some horn-rimmed glass wearing MCP dreams up and hope for the best.

Maybe subsidizing ADUs is the most efficient use of affordable housing dollars. ADUs get developed on existing properties so they check all the right planning boxes (urban infill, densification, etc). But if you never put them next to something else and ask, “dollar for dollar what’s the better deal?” then you can’t really know.

Question 4: How many ADUs would we get without the program

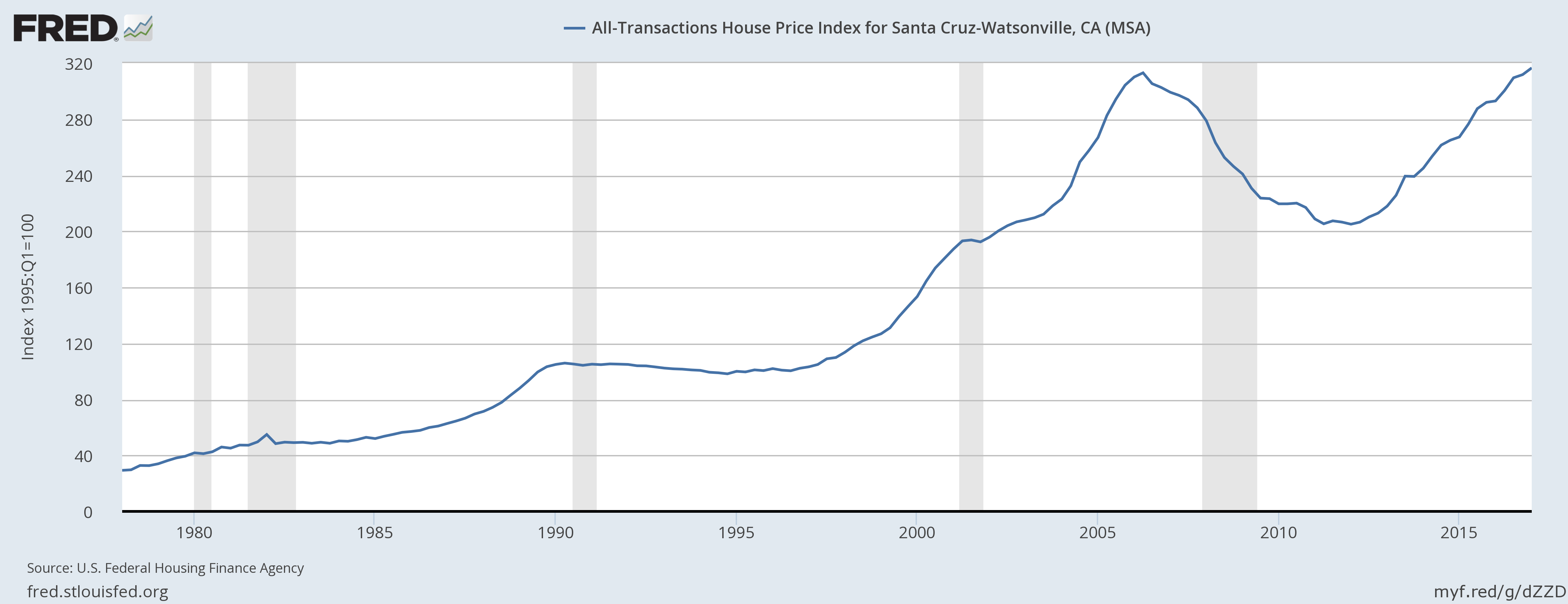

There is a chart you can find here, on page 4 showing the growth in ADU permits for Santa Cruz between 2001 and 2006. The ADU program began in 2003 so 2001 and 2002 are labeled the ‘Pre-Program Years.’ In 2001 and 2002 there appear to have been around 10 ADU building permits granted and from 2004 to 2006 it looks like an average of around 40/year. This is a pretty remarkable increase and, if we knew nothing else about what was happening in the world during this time, it would seem really convincing that the ADU program was effective at increasing ADU development. The problem is that, the Case Shiller Homeprice index for Santa Cruz - Watsonville began a remarkable increase in Q4 2001 that lasted until around Q2 of 2006.

So, while ADU permitting undeniably increased between 2001-2002 and 2003-2006, it is also true that home prices were appreciating at near meteroic rates during this time period…making it very difficult to attribute the growth in ADU permitting exclusively to the ADU Program.

Question 5: Subsidy or Command-and-Control?

Let me propose a straw-man alternative to subsidizing ADU development in exchange for renting below market:

Rather than subsidize development, what if we said, no new ADUs will be permitted unless the owner agrees to rent below market. This is a command-and-control policy as opposed to a subsidy. This isn’t a particularly well thought out alternative but it’s bluntness will make for a good example I think.

Some quick facts:

- According to multiple sources here and here ADU construction costs generally range from 50,000 to 80,000.

- The current ADU program in Santa Cruz offers you subsidies (page 48) if you rent as affordable to a tennent making 80% of Area Median Income or less (1,060/month for a single individual or 1,211 for a couple).

- A 10 year loan in the amount of 80,000 at 5.25% interest would obligate one to 858/month in payments

This means that an individual financing the construction of a 67,000 ADU (67,000 construction cost + 13,000 permit fees = 80,000 loan) could satisfy the affordable housing rental rates and still make around 150/month. Additionally, this hypothetical individual would have added value to their home thereby increasing their wealth for free.

The benefit of the subsidy versus the command-and-control approach is that when you subsidize something you get more of it. But, in this case, how much more or how much less matters a lot. Let’s say that with the subsidy we expect 50 ADUs to be permitted next year and 40 of them will be committed to be offered as affordable housing defined as follows:

\[rent=\frac{(0.8)(AMI)}{12}*0.3\]Let’s say that without the subsidy we expect the number of permits to fall by half.

Program Units Affordable_Units GovRev

1 Subsidy 50 40 0

2 Command-and-Control 25 25 325000

Under the subsidy we get more total units and more affordable units. Under Command-and-Control we get half the number of units and 15 fewer affordable units but 100% of units are offered as affordable housing and we get the 13,000 USD permitting fee on each unit, which raises 325,000 USD of public money.

The 325,000 is the real kicker because under Command-and-Control we get 15 fewer units but we get cash. That means we could take those 15 people that would have been offered affordable housing under the subsidy program and offer them 21,666 cash money instead.

My numbers are made-up. I get that. But it’s also sort of my point. I would love for somebody to replace my bad numbers with the right ones and tell me if this subsidy for ADU development still looks awesome next to a straw-man alternative.

Some pretty basic arithmetic tells me that homeowners would still make money if they were forced to rent their ADU below market as a condition of development. So I find it pretty unbelievable that ADU development would drop to 0 if the subsidy went away. I’d love to see a decent analysis of what impact dropping the subsidy would have on the supply of ADUs.

Question 6: Where can I find informed discussion of which low income populations benefit from ADUs and how?

The bar chart I referenced above shows the number of ADUs permitted from 2001 to 2006. It doesn’t shed any light on how many of those were supplied to low-income renters at affordable rates (below 50 percent or 50 - 80 percent of AMI).

The Santa Cruz Housing Element identifies the following population groups that warrant particular attention because the existing housing market has not adequately met their housing needs:

- seniors

- people who are homeless

- large households (5+ people)

- people with disabilities

- female headed households

- farm worker households

Seniors are a group from this list that reap rather obvious potential benefits from subsidized ADU construction - seniors are often looking to downsize and seniors, particularly those on fixed incomes in Santa Cruz County, probably find the supply of smaller, affordable units pretty sparse.

Again, to their credit, the folks behind the Santa Cruz Housing Element have done a great job:

- discussing the specific housing needs of seniors and particularly low income seniors, and

- exploring the types of sustainable development that can benefit seniors, and

- providing a comprehensive inventory of subsidized senior rentals (Housing Elements, pg. 4-40, Table 4.3.8 and surrounding text)

What I have not found in the Housing Element, or Sustainable Santa Cruz Plan, or RHNA, etc. is a discussion of how large the affordable housing need is among seniors relative to low income families.

So to recap a bit:

-

Seniors, particularly low income seniors, can benefit directly from subsidized ADU development that is earmarked for affordable housing…and we have a good idea what the current inventory of subsidized senior housing looks like…but we don’t know exactly how pervasive the current need for affordable housing is among seniors relative to other need groups.

-

Low income singles, particular those with disabilities, or couples can probably also benefit directly from subsidized ADU construction…but the same caveat applies here as in Item 1: we don’t have very solid supply targets set for this group.

-

Existing homeowners (a relatively wealthy group by definition in Santa Cruz) benefit from ADU subsidy programs directly, financially, and in ways that are certain and quantifiable.

-

Low income families (or anyone else that needs more than 640 sq. ft. of space) may benefit to the extent that adding to the existing rental stock (affordable or otherwise) puts downward pressure on rental rates.

Summary

I can wrap this one up pretty quickly:

ADU development as policy choice has some nice theoretical benefits:

- takes advantage of existing developed land (encourages densification)

- provides diversity and increases choice in the rental market (most commercial rental units are larger than the 400 - 600 sq. ft that is standard among ADUs)

- increases overall supply of rental units which can help stablize rents in areas of rapid rent inflation

Many of the theoretical benefits actually address housing issues unique and specific to Santa Cruz

- existing home values are high for a variety of reasons but amenity value (Santa Cruz has a lot of green belt, scenic land, and coastal access) is a big contributor. ADU development can add to the rental supply without additional land development that might erode amenity values of existing properties.

- Santa Cruz is a small city with a large public university. Over 5,000 graduate students compete with permanent residents for housing. It is possible that even increasing market rate ADU supply can help low income families by taking some of these (relatively affluent, mostly single) bidders out of the market for larger rentals.

ADU development strategies are also kind of a ‘path of least resistence’ type strategy. They are politically popular because they give money to homeowners and don’t take anything really obvious away from other groups…so they look like a Pareto Improving policy.

In theory and concept subsidizing ADU development seems like a strategy that might warrant a prominent place in our Housing Plan. However, ADU subsidies cost money. There are real financial and opportunity costs (foregone municipal revenues). Evaluating just how much public money we should be devoting to a subsidized ADU program is where we need to put an ADU subsidy next to something else and ask, “how does it stack up empirically?”

My research suggests this is not being done. This post obviously does not provide a thorough evaluation of ADU subsidies in Santa Cruz but I think it poses a few straightforward questions that could be used to structure a more thorough evaluation.

Finally, before you say, “If it’s so straightforward, why don’t you do a thorough analysis then?” recognize that Santa Cruz County has a habit of employing a rather slick looking consulting outfit called BAE Urban Economics (who despite have ‘Economics’ in the name appears to have 0 economists on staff). Surely some of the 200-300/hour of our public money getting funneled their way for Economic Vitality Studies and Economic Trends Reports could buy us a decent Housing Policy Analysis. If not, I’d be happy to do it for half of whatever BAE is charging.